Behind the Scenes

Resistance on the Plinth: the why of it

Written by Liz Crow

A version of this article appears in the Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies, March 2011.

I am sitting in the basket of a cherry picker, draped in an ancient white bedspread, being driven forward on a JCB. Through the thick fabric I see spots of bright light and the amber of the vehicle’s warning strobe. We begin to rise and I am pitched into that moment when they close the plane door and there’s no going back; only a hundred times magnified.

So up we rise and rise, high above the plinth, before coming in to land. “Freaky, freaky”, says the previous plinther as the wrapped figure draws closer. Spotting the wheels of my chair, she subsides into mortified giggles. The cherry picker docks at the plinth and she welcomes me with a “Hello under there, whatever you are.”

I am wheeled backwards down the slope of the basket and onto the plinth, except that – oops – running out of time, I haven’t briefed anyone on how and immediately plunge into freefall, arse over tit. I lie there in a white shroud, my legs in the air, a foot away from a two-and-a-half storey drop. Now there is no going back.

The One & Other project was announced a couple of months earlier. Taking place on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, home to temporary works of art, sculptor Anthony Gormley set out to create a “living monument that captures modern Britain”. For 100 consecutive days, 2400 people would each spend one hour, on their own, high up on the plinth.

In a public space bordered by military and valedictory monuments, there was something about the ordinariness, smallness and aliveness of a diversity of people redefining the space that touched me. In the words of Gormley, “Maybe we’ll discover what we really care about, what our hopes and fears are for now and for the future.”

While I lacked both the exhibitionism and courage to be a part of any such thing, we needed to make sure disabled people got up there. So I told my friends, put out a few notices, signed up my own name. When I was picked in the monthly draw, my bluff was called.

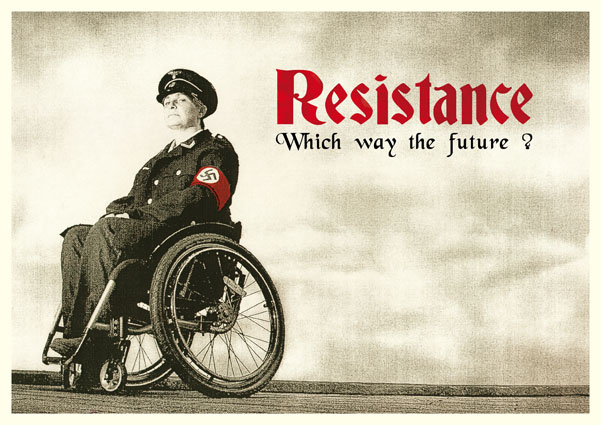

One & Other arrived at a time when I had spent 14 years deliberating and two years creating Resistance, a touring installation about the Nazi campaign against disabled people and its contemporary relevance. It coincided with the 70th anniversary of the start of Aktion T4, the little-known first phase of systematic mass-murder by the Nazis, which targeted disabled people and became the blueprint for the Final Solution to wipe out Jews, gay people, gypsies and other social and political groups. Disabled people’s resistance was pivotal in bringing the episode to a close. And even as I longed to lie down on the plinth and gaze up to the stars, I knew this was a moment that would never present itself to me again and it had to be well used.

I meet my marketing mentor, Ros Fry and we mull and wrangle over what I might do until… oh, how did we get here, because suddenly, in a throw away comment, we have an idea. How about going up in Nazi uniform? And we laugh, because even as we know it is beyond outrageous, beyond bold, it is also crystal that this is it. As a wheelchair user, I will bring together two potent and contradictory images – the swastika and the wheelchair – like repelling magnets and they will be displayed on all that the plinth represents: elevation, preservation, triumphalism.

On the internet, I find a photograph of a young Asian man, wearing a bright red t-shirt, a large swastika on his chest*. The image hits in three, almost-instantaneous, blows. First is the swastika, then the man’s skin tone and then the contradiction. In the blink of an eye, it shifts the ground from under me. He stands facing the camera, smiling. And it is all – everything about it – instantly wrong; almost an inner ear, out-of-balance sensation that keeps me questioning long after I have torn myself from the screen.

How easy it is simply to equate the swastika with evil and stop at that, but how much more intriguing it will be to take an image that represents one thing and, by changing its context, transform its meaning and use it to confront itself.

If my image on the plinth can achieve that, it will be extraordinary.

But in the midst of all this, there is me. It is not every day you dress in the symbol of hate and loathing. What if people look but forget to think? What if they think the uniform is me? As a friend puts it, am I prepared to become a centrefold for the Brtish National Party? I have no way to predict whether people will grasp the image – or whether they will throw bottles. A summer’s evening, pub closing time, is a risky time to find out.

It is odd to be doing something so different (so confrontational, so exposed) from my character. I shudder at the thought of wearing that uniform. I try to convince myself it is just fabric, but the meaning of the fabric, the intent within it, puts lie to that. I would happily recruit an actor to the role, but the place is non-transferable, so it’s me or no one.

I want to draw attention to this hidden history and commemorate the people who died in it. I want to make apparent the link between this extreme, stark episode and now. I want to create a starting point, a moment, where the onlooker might think what it means for them. My job is to knock people off balance, to pull the rug from under them, enough that they ask questions. The dialogue is for others to have; whilst some plinthers talk to their audiences, I make a decision to maintain silence and stillness so that the image dominates. This is a political work, effected through performance. The power will lie in creating an image that is static, yet live, and inviting response.

As with any work, there will be a point of letting go, a leap of trust. I can form the work, but it will be completed by its audience; it is they who will define its meaning (again and again). As I place this image in the public sphere, I make myself dependent on the audience’s willingness to engage; if they do, there is potential for it to soar.

I am joined by Art Director Dave Paul, who sources uniform and props. Together, we discuss design, choreography and timings, weather contingency, leaflets, press releases and web back-up. I map out the Square for its dimensions and attempt to predict visibility from different distances and angles. It is vital that my chair is in view.

I will be performing to two audiences. The first is in the public space, with the audience local, directly below in the Square, and the work performed live. The second, much larger, international audience will be via footage on the One & Other website, with camera angles mediated by their editors, streamed live and available for subsequent download in a permanent resource. The image needs to work for both the ‘upward gaze’ and the multiple cameras sited level with the plinth.

Clair Lewis of Direct Action Network (DAN) organises support on the ground. On the One & Other website, each plinther is allocated a page where they can introduce themselves and this gives me a chance to give a context to the work that will sit alongside the footage of my hour. Independent filmmaker Barry Seddon will be there on the night to make a short film4 about the work and its larger context for distribution on YouTube.

Practicalities help distract from the bigger fears, but I am afraid – enough that, the evening before, I realise I cannot do this. I am afraid of hurting people and I don’t want to be hurt.

Anxiety creates its own momentum; to stop it running out of control requires returning to the why – the absolute essence of what I am doing. The morning of my plinth day, a conversation takes me back to the beginning. I find myself talking with passion about the rise in hate crime, a population larger than Cardiff in institutions, children excluded from school, pre-natal screening, the race to assisted suicide legislation and the why is clear.

I try the uniform for size, but the jacket is so huge that it looks like a bad bandleader’s uniform. I face the possibility of creating a comedy act, knowing that that could be the worst thing of all. I ricochet once more: on-off, on-off. And then I remember the art director’s trick of gathering up surplus costume fabric in a bulldog clip to create a shape. The uniform is in place. The person assisting me steps back to look. Until now, the image has been expressed through words; now it is real and any uncertainty about its power melts away. “You have to do this,” she says. It is on.

Arriving some time before my slot, the sky is half-light, the spotlights on the plinth just on, the Square heaving on a warm Saturday night in August, and the plinth is so godamn high.

In the One & Other offices, we go through procedures and release forms in an atmosphere of disconcerting calm. Do they realise what I am doing up there? Oh yes, everyone’s been briefed: production crew, ground staff, webstream editors. Security is on alert and will surround the cherry picker as it crosses the Square.

Up on the plinth, the cherry picker moves away, leaving me there, alone and up above the Square. I feel the very edges of my heart, the muscular pumping of it, booming in my chest. And I gaze ahead through the fabric to the spots of light and down to my watch, thinking hold it, hold it, keep still, keep covered; another minute, another, and another after that, taking it in increments.

I know there is a collective holding of breath between me and my supporters in the Square, not all of whom know what will be revealed, only that it will be a representation of disability that goes against expectation. The popular perception is of disability as ‘worthy’ or ‘depressing’. Here is a community that longs for a counterpoint, an image that will cause passersby to look, and look again.

Ten minutes in and it is time to make them look. I throw off the shroud from my head and shoulders and body and chair, place the hat firmly on my head and now there’s a Nazi on the plinth, a Nazi with a wheelchair. And I look ahead, face set, half-focused far distance, no interaction with the onlookers; a symbol intended to steal their breath away.

Beyond the Square, an energetic virtual dialogue springs into action. One & Other staff will later report that Twitter “went ballistic”, the first tweet shouting: “WTF?” and a whole flurry of debate and conversation tracks the hour: the what and the why and how to find out more. The image has knocked people off balance, pulled the rug, and the dialogue is flowing.

At ground level, a team of supporters has made an informal ring around the plinth, so that each time anyone comes forward an explanation is ready. And people linger, watching and debating and sharing their experiences. When the leaflets run out, strangers pass them on to strangers and talk to each other about why. Clair shouts up to me “It’s alright Liz, they all get it!”

Revealing the next phase of the image, I pull out a flag from under my chair. On the flag are the words, black on red, of a verse by the anti-Nazi theologian Pastor Martin Niemöller. The version best known begins ‘First they came for the Jews but I did not speak out because I was not a Jew… Then they came for me and there was nobody left to speak out for me’. There is also a version that refers to the targeting of disabled people, with the words ‘First they came for sick, the so-called incurables’, and this is the version I use.

That recognition of a community’s experience, historical or contemporary, runs through the work and the collective bond was felt by disabled people in the Square and internationally. A presenter on BBC Ouch’s talkshow spoke of being in the Square and “before I knew it, I was giving out leaflets… it was lovely to be sucked into it”. A group of disabled people in Brisbane emailed to say they were gathered round a computer at 6am to watch communally. On the One & Other site, a disabled person from the Square wrote “To be part of large group of Proud Disabled People gave me ‘HOPE’. In a time of uncertainty and upheaval in our lives, coming together… gave me a very warm feeling.”

And as I raise the flag, a breeze unfurls the fabric high above the Square.

Beyond the plinth hour, the dialogue will continue through Twitter, Facebook, websites, blogs and far beyond. Comments on the One & Other website include “Your silent clarity caused me (I hope amongst many others) to question further my previous over-idealistic beliefs,” whilst a supporter from the Square writes that the hour “sparked lots of discussion and support amongst the people there who were initially surprised and confused at the striking and challenging image… People got it and knowing you are against nazi ideals made them smile… At least a thousand people were given a message most of them had never heard before. I hope they pass it on!”

It is time to shed that uniform, so I unbutton the jacket and pull off the armband, holding it aloft, screwing it up in my hands and casting it down to the plinth. I discard the jacket, bundled and crumpled and thrown down in disgust. I slide my loosely laced boots from my feet and sit, black trousers, black t-shirt, barefoot, to wave the flag, and it feels good.

With my red flag, I begin to emerge from the symbol. The breeze is snappy, so I raise that flag and steer it round so that it is visible from every angle. People passing by on the pavement alongside the Square stop for minutes at a time to read the text and contemplate the image.

The clock moves slowly; its speed varies. I mainly look up and fix on distant objects. As the hands turn, I feel distinctly odd; the building to my left, with its floodlit curved facade, begins to flip, convex-concave, convex-concave. I return to a far-distance gaze, checking on the flag, lining it up for passersby and camera, and breathing. When I catch the amber flash of the cherry picker making its way across the Square, I am ready, and the hour has also sped by.

My heart takes a week to return to its usual rate.

When I look back to that night, I feel the turmoil every inch of the way. While the image very quickly became not-really-me, it has lost none of its danger.

That danger lies in the possibility of misinterpretation, all those fears I barely contained in the run-up to the plinth. Yet it is the danger of the image that is its power.

Repeatedly, my work tells me that political change is driven by emotional connection; that it is the individual’s ‘buy in’ to an idea, or ideal, that opens them to becoming a part of change.

This image demands response; it keeps people looking, bombarding them with questions and confronting them with information and meanings they may never have encountered before. And as they look and consider and return again, that emotional connection builds. A softer image might raise the same questions, but is easily shrugged off; the visceral impact of this image and the dissonance it produces continue to demand.

An image can’t make social and political change, but it can open a door. My task that night was to create a starting point, a moment where the onlooker would begin to ask questions. The point at which the onlooker responds is the point at which others can step in – the activists, the academics, the campaigners, all of us involved in that much larger process of change can use that opening.

In Trafalgar Square, this is what the supporters did. Each time an onlooker responded with “What the -?”, they moved towards them to say “This is why”. They listened and talked, provided clarity and direction and, as they built upon the emotional connection, people began to shift from onlooker to ally.

The image didn’t finish the night it met an audience. As it continues to circulate and meet new audiences, my hope is that others will do what the supporters in the Square did and capitalise on that small opening. From the image-maker to the supporter to the onlooker, this is a process of collaboration.

______

* Although the swastika is an ancient sacred symbol that has existed across many cultures since prehistory, symbolising peace, life and good luck, it was appropriated by Hitler for the Nazi party and has become widely recognised as a symbol of hate. There are campaigns to reinstate its original meaning. However, the young man in the photograph wore the tilted, counter-clockwise version printed in black on a white circular background and on a red t-shirt, a combination usually associated with Nazi usage.

For further discussion see: Quinn, M (1994) The Swastika: Constructing the Symbol, Routledge.